Clean Space - The Moon does NOT orbit the Earth

In this article I’m going to delve into some of the science behind the exploration aspects of Clean Space, and perhaps tackle a couple misconceptions that you and I may share, such as the title of this article. Nothing I’m presenting here is ground-breaking, but I hope you find some of the facts interesting as we recap ourselves on those awful trigonometry lessons or physics classes of your past! Don’t be put off, I literally had no formal education beyond Secondary School in the UK (10th grade - or sophomore I believe it’s called - in the US), so there should be nothing here most layman can’t grasp. I’ll apologise now, because that same education (or lack thereof) will no doubt account for some level of ignorance and subsequent mistakes in this article; if the actual smart people fancy lending me some pointers in the comments section, I’d be very grateful!

Moon orbiting the Sun, locked to the Earth. Image from Wiki

As is hopefully evident from the image above, the Earth-Moon system is better considered as a binary planet orbiting the sun than the more typical images depicting Moon’s orbit of Earth. The acceleration of gravity applied to the Moon by the Sun(~0.00596m/s$^2$) is actually twice that of the force applied to the moon from Earth (~0.0026967m/s$^2$).

Clean Space

For those of you new here or whom glazed over the Clean Space Introduction, Clean Space is the game I’m working on. I’ve been defining the game in day dreams and thought for at least a decade, but finally decided I had the capacity to make it a reality about 6 months ago. I’ve barely scratched the surface for game content so far, but the planning is well underway and there are some substantial amounts of code tucked away in private repositories as I work through the early stages.

I have built a great support group so far to assist with design decisions, discussions over theoretical physics, and have several people keen to help out with (or at least peek at) the codebase. Despite a great deal of advice to the contrary (and apparent lack of sane judgement), my first game is set to be a massive undertaking. When asked, I tend to repeat that I don’t believe the game will even be in demo stages for at least another 24 months. However, I plan to share as much of the journey as I can through blogs like these, the odd technical demonstration, and a couple game design revelations along the way.

Goal

I’ll begin by describing what it is I set out to achieve here, and as best I can, describe the journey I took. I knew when I first decided on the scale and plausibility of Clean Space that I would be spending an awful lot of time learning and not enough time coding. This particular subject was probably one of the most difficult to overcome so far, but puts me in great stead for future challenges by providing a much improved foundation of orbital mechanics (that’s rather important in a space game), and also adjusted corrected my expectations for the future.

In short, I wanted to flesh out the technical and scientific realities of exploring a stellar system. So yeh, there’s the first fun fact:

Our solar system is the ONLY solar system; everything else is a stellar or star system.

NB: I actually refer to other systems as star systems normally (since learning the above), but calling them stellar systems hopefully caught your attention. Our star system is named for our star, whose Latin name is “Sol” (Solar).

Of course, we tend to confuse ourselves with a naming quite a lot (the “moon”, the “sun” and so forth), but correcting those neural pathways of our childhood (and the adult life of a layman) can be trickier than you might think. If you continue to read these articles, prepare yourself for that particular aspect. Whilst we can intellectually accept these corrections and are often already aware of them, it takes a long time before it becomes natural. The number and size of differences between the over-simiplified lessons of our youth and subsequent assumptions are truly staggering. Don’t be at all surprised though if I misrepresent something because I’ve fallen pray to the more natural tendencies myself!

Science

While we’ve made incredible progress regarding exploration of our own Star System here on Earth over the last few millenia, we haven’t actually explored all that much of the Solar System. Being a space game and the limited progress of our own spacefaring capabilities (though a massive thanks and high-five to efforts such as SpaceX!), one of the hardest aspects of developing Clean Space is balancing between real world physics, and the theoretical science that the game lends itself to. I’ve played a lot of games, and a great deal of those have been 4X games. In that time, I’ve seen nothing come as close to real world science as Clean Space, except perhaps Kerbal Space Program (though orders of magnitude differences in scale).

There are of course various space simulators that better resemble the science we’re trying to achieve here, though through very different approaches in that they are exactly that, space simulators, not so much games.

I’m going to be intentionally ambiguous in some areas regarding the game design (and plans) for Clean Space. I’ll give away plenty of hints throughout this article, but I want to hold some details back for some fun surprises down the line, plus retain freedom to go back and change any decisions made thus far. However, to get the ball rolling, let’s postulate that through whatever technological miracle, that a spacecraft of Human (or Terran) design finds itself in an unexplored star system with sufficient capacity to move about said system in a timely manner. It is on a scientific mission to ascertain as much detail as possible about the celestial bodies it can discover within the system to improve upon observations that may have been made across the vast distance between this unexplored system, and the craft’s originating star system.

Let’s also assume, that the unexplored system in question (through the perspective of the vehicle’s owners), is the solar system (i.e. the star system you and I are in right now). That isn’t my giving away lore for Clean Space, it’s simply so that we can compare assertations and use real world examples to confirm the findings of this exploration vehicle.

Gravity

I’m not going to try to teach people to suck eggs, but to ensure my readers (you) have the basics under wraps, I’ll very briefly mention gravity.

The force that attracts a physical body towards any other physical body.

The greater the mass, the greater the gravity. We actually tend to refer to that resulting force as an acceleration, so that the force of gravity on the surface of Earth, for example, is 9.78 to 9.83 m/s$^2$ (meters per second per second). The force of gravity is incredibly weak despite the profound effect it has on our day to day lives, which might explain why it’s so difficult to measure the gravitational constant.

This is perhaps an interesting subject; when I began working on Clean Space I simply picked the first value for the gravitational constant I could find on wiki, and got on with my life. I recently revisited the fundamental physics of the game engine (Clean Engine) and was dismayed by the huge number of supposed constants I was coming across, leading to a very interesting article by Lisa Zyga. For the sake of the remainder of this article however, as interesting as toying with the idea of a variable gravitational constant might be (that’s a hint towards a future article), we’ll use the value 6.673889E-11.

NB: For those that have forgotten how exponents work, the E can be replaced with , or simply move the decimal point the given number of digits either to the right for positive, or left for negative exponents.

Law of Cosines

So, our exploration ship has attained orbit around Earth. It’s sensors have located a satellite body (the Moon), and it’s time to get our geek on. So, what information can we get from observing these two objects?

Well, first and foremost, the spacecraft is able to get the distance from itself to the Earth and the Moon (even modern day technology can achieve this so I won’t go into detail). From it’s position, it should also be able to extrapolate the radius of both bodies which is required to get the distance from the vehicle to the centre of both the Earth and Moon, not simply the distance from itself to the surface of each body as would be measured (the calculation could be done using the surfaces if required, but it becomes slightly more complicated).

Given these little facts, we can calculate the distance between the Earth and Moon easily enough, using the law of cosines: $c^2 = a^2 + b^2 - 2ab \cdot cos(C)$ where C denotes the angle between a (the length between Earth and the vehicle) and b (the length between the Moon and the vehicle), opposite from c (the distance between Earth and Moon).

Note that the case of a or A is important. Lowercase for a length, uppercase for an angle.

You may also notice that the Law of Cosines shares a striking resemblance with Pythagorean theorem. While Pythagoras’ theorem is intended for right triangles, the Law of Cosines works with any triangles, which is made more evident when you realise that $cos(90) = 0$, which means for right triangles, the $2ab \cdot cos(C)$ can essentially be ignored, bringing us back to Pyhtagoras’ theorem.

We have at this point the distance between each body, allowing us to use the law of sines to get the 2 remaining angles if required (${a \over sin A} = {b \over sin B} = {c \over sin C} = d$ where d is the diameter of the triangle’s circumcircle). With the 3 lengths and 3 angles of the triangle between our spacecraft, the Earth, and the Moon, we can begin delving into orbital mechanics.

Kepler

Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer, and astrologer. He is well known for a number of published works, not least that which contained Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. The wiki article linked there is a bit mind blowing at first glance, fortunately there are much simpler articles to reference should you want to follow along. In essence though, the laws provide mechanisms to ascertain:

Orbital Speed

The speed at which the satellite (Moon) moves:

where G is the gravitational constant we discussed earlier, M is the mass of the body being orbited (Earth), and R is the radius of orbit for the satellite body (the distance between the centre of the Earth and the centre of the Moon that we discovered above). See how this is all coming together yet?

NB: The above only works for a circular orbit, but let’s keep this first lesson simple.

Acceleration

The acceleration of gravity on the satellite (Moon):

Orbital Period

And finally, the length of time it takes for the satellite to complete an orbit:

π is pi for those that may have forgotten.

NB: It’s worth noting that there are a great number of assumptions necessary for the rudimentary calculations above to work accurately, such as the observed bodies being spherical (which isn’t always the case in the real world). However, given this game universe is one of my own making, I do have the luxury of enforcing these assumptions as contraints, should I choose.

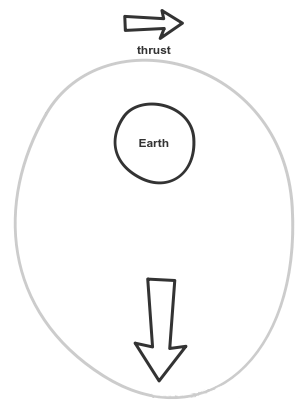

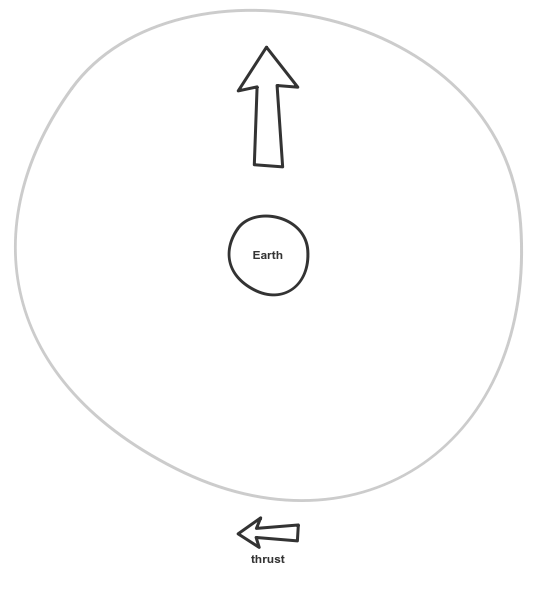

Celestial Mechanics

For anyone that’s managed to get a vehicle into Kerbin orbit in the game Kerbal Space Program, the basic concepts of orbital manoeuvres have, I’m sure, made themselves aware. If a vehicle is orbiting a body (be it a planet, a star, anything), to attain a lower (closer) orbit, you don’t burn towards the body, like you might think. Instead, you thurst in the opposite direction to your orbital trajectory which is known as retrograde, and similarly thrust prograde to attain a higher (further) orbit. What’s more interesting is that, assuming you started in a circular orbit, applying thrust will most effect the opposite side of your orbit, pushing it away or towards the body being orbited (depending on whether your thrust is prograde or retrograde respectively), changing the eccentricity of the orbit either towards a collision (suborbital), or a parabolic/hyperbolic escape trajectory.

Therefore, to go from a circular orbit, to another circular orbit, you would typically require 2 periods of thrust. One that changes the opposite side of your orbit, which you then coast around to, before thrusting again to circularise the orbit.

Putting the pieces together

If you combine all of the above, there’s a great number of things our exploration spacecraft can observe, measure, extrapolate, and assume. By plotting the orbital trajectory of bodies, we can ascertain the gravitational parameters (μ) of the bodies involved. If the gravitational constant is known, we can extrapolate the mass of bodies. We might even begin to make assumptions of density from observed mass (versus body volume) to take a guess at heavy metal likelihoods.

There are a great many ways exploration can and will effect the game, and it will evidently be crucial to have a basic understanding to be at all competent in the game. I love the prospect of teaching (hopefully not too incorrectly) physics and astrology to people playing the game, though can hopefully make it fun. So, let’s see how all this science might apply to Clean Space.

Independent Observation

Whilst Clean Space is based largely on real world physics, I don’t intend to force all of the above down the throats of a player. For all the scientific simulation that goes on, I know that this game needs to be much more game than second job. At the same time, I want to reward those that do take the time to understand the physics.

So why does all of the above science and laborious equations matter?

Actually, the above is a very simple basis to get your toes wet…

There are 2 reasons. The first, as I’m sure you could guess, is that the game engine for Clean Space uses all this science to simulate the game universe (no pun intended). Using mechanisms like the above (typically using functions over time to achieve the performance required), the engine intermingles real world physics with vasts amount of theoretical physics. This is a difficult task, and at least in part explains why the development time of the game will go on for years.

However, the second and much more fun reason, is that unlike any game I’ve ever played, Clean Space does not simply reveal these facts about the universe to the player. Moreover, it doesn’t reveal these facts to the AI!

Think about that for a moment. No, really. Consider the implications.

I mentioned in a previous article the limitations that would be enforced upon the world with regards to the speed of information. That in itself makes for an interesting mechanic that I don’t believe I’ve seen in other games. But this little revelation brings upon a whole new scale.

Research

The game design behind research in Clean Living is so unique that it’ll require at least one article unto itself to fully describe. However, consider for a moment that your typical technology tree isn’t rail-roaded. Not only you, but all the AI of your faction/race has but a foundation knowledge when the game begins. It understands all the real world science we know of today, and a limited amount of the aforementioned theoretical intermingling.

However, to learn more about the universe, and to increase one’s understanding and technology, you can’t simply sink some resource into a hypothetical project and after an allotted time have something revealed to you by the game engine. You actually have to explore, make observations that challenge your current [mis]understanding of the universe about you. You have to design, fabricate, and trial experimental equipment, and only through subsequent observations and refining of techniques can you hope to learn more about the theoretical physics the sneaky programmer has put into the world.

Exploration

The only scientific consequence I’ve come across when exploring in other games is perhaps stumbling across some artifact that provides some form of boost to the explorer. In Clean Space, the role of exploration will be like nothing I’ve seen simulated before.

Forming adequate information to accurately and efficiently perform astrogation is still crucial, more so than you might expect given how forcibly the physics apply themselves, and just how complicated that is even when you have all the facts. Any time a spacecraft finds itself veering off of a projected course, it isn’t a mistake in the system; it’s an observation of the undiscovered.

Summary

I truly wish I had the time to put my money where my mouth is, but the real world comes first and we’ve all got bills to pay. Hopefully, it’s evident just how magnificent a task I’ve set for myself. Whilst I hope the prospect excites you, you’re just going to have to hang in there for evidence of all this posturing to come to fruition.

For the same reason it’s much too early to reveal any gameplay footage, it’s also the perfect time to submit your ideas. They don’t need to be scientifically sound - trust me, mine are dubious at best. But if there’s something you’d like to add, something you’d like to see in Clean Space, the sooner the better. Drop a comment below or use one of the icons at the bottom of the page to contact me!