First Look at 'My Tested ASP.NET' for ASP.NET Core

I was recently contacted by Ivaylo Kenov asking if I could take the time to review his new fluent testing framework for ASP.NET Core MVC. I hadn’t come across any of Ivaylo’s work before, but tend to enjoy evaluating new technologies and frameworks so decided to share my review.

The sample code referred to below can be found here.

Pricing

I want to get this out of the way early, but it’s worth noting that ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’, whilst free for a many uses, does have a price tag. The not-insignificant cost will surely drive expectations ever higher for paying customers, which having conversed with Ivaylo considerably since first drafting this article, I’m sure will be met in terms of support. I do hope though that those with paid packages which include the ability to request priority features and bug fixes do not hamper progress of the library or detract value from it. After all, if a paying customer demands a bad feature which by rights is included in their package, will Ivaylo be able to say no, as would normally be the case in well maintained open source projects?

On the flip side, I’m glad to see there does not appear to be much of a feature difference between paid and non-paid; the free version is limited to no more than 500 assertions per test project, whilst the paid version has no such limit. You can however have an infinite number of test projects, so in theory, you can still use the library for free.

The cost, it seems, is mostly for sake of licensing and some additional support. However, all of the alternatives I’ve personally used and describe below are completely free, so the cost of ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ will definitely be held against it.

Overview

Having scanned the very fancy website (so fancy in fact, that my poor display driver crashed on a works machine), I get the impression that the ‘My Tested *‘ series has been around for a while. I was surprised that I haven’t heard of the libraries before, especially after some research (and tactful nudges from Ivaylo since) revealed that the library has been both featured in a .Net Blog, and more recently added to the MVC Repository. Hopefully this goes towards showing some maturity (and excellent marketing) for the product and not the relative obscurity of my own experience.

Still, I was surprised - and disappointed - to see that the aforementioned pricing model was only used for the new ASP.NET Core MVC (Preview) iteration, not the previous test frameworks.

At a glance, the framework appears to encompass two key areas:

- Instantiation and execution of the ASP Pipeline (though it’s hard to tell exactly how involved this is from the website).

- Fluent Assertions (not to be mistaken for the well know Fluent Assertions framework).

Fluent Assertions

I’ll say now that I’m pretty disappointed that the Fluent Assertions aspect of the ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ framework wasn’t created as an extension of the official Fluent Assertions Library (apologies for the ambiguities in that statement). I converse with Dennis Doomen (author of Fluent Assertions) regularly on twitter, through his blog, and every now and then via the Fluent Assertions Gitter Chat. Both Ivaylo and Dennis are great guys, so I hope they can get their heads together and work something out.

There are of course other fluent testing libraries such as Shouldly whom I don’t have any personal contact with. However, whilst I periodically review my personal technology choices, I haven’t yet strayed from Fluent Assertions since first discovering it some years ago.

Whatever the reasoning behind the decisions made thus far, I will be comparing the functionality of ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ to mechanisms I would use without it, which for me at least, typically involves using the Fluent Assertions NuGet Package. It is worth mentioning (and praise) however, that whilst the library does not have any formal support for other fluent libraries yet, it is in the pipeline.

ASP.NET Core Pipeline Testing

The second half of the ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ library appears to be responsible for running your web site to some extent. This is a key point and one I intend to verify as thoroughly as limited time permits.

For better or for worse, several of the websites I’ve helped get into production, from ASP.NET 5 RC1, ASP.NET Core RC2, through to ASP.Net Core RTM, utlise slightly advanced features, digging deep into the Middleware and intricacies of MVC (as you may recall from my previous article on action conflict resolution). To test these features I’ve always - since becoming aware of it - used the Microsoft Test Host which has the benefits of not only being simple, but being the tool of choice for the ASP.NET Team.

It’s important to note here the difference between Integration testing for which the MS Test Host is intended, and Unit testing. It can be simple to test the code within a Controller method through Unit testing, but when you start involving routing attributes, constraints, model binding, authorization, and any number of additional MVC features, most of which will rely upon MVC features we tend to take for granted, things become much more complicated. Both the approaches I show below are able to account for these additional features, though I’ve yet to examine just how far ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ is able to go considering it does not take the heavy approach of starting a Test Server, instead tying itself directly into the services responsbile for these MVC features.

Comparison

I’m going to run through a sample scenario for the remainder of this article, and plan to add at least one follow up article with additional comparisons. I’ll be testing functionality using both the alternatives I’ve listed, and ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ framework

Note: having typed the framework name ‘My…’ several times now, I can’t help but think a catchy and much shorter name wouldn’t have gone amiss!

Routing Test

I’m going to try to be unbias and as fair as possible in my choice of tests to compare. The first test I picked is a simple routing example taken from the ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ website. This was the first test I noticed on the website, however, I’ve since spoken with Ivaylo and agree that whilst this is a supported scenario, the library is much more conversant with Controller tests. For the time being though, here is the routing test I copied from the website:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

[Fact]

public void MyControllerShouldHaveRouteForActionWithId()

{

MyMvc

.Routes()

.ShouldMap(request => request

.WithMethod(HttpMethod.Post)

.WithPath("/My/Action/1"))

.To<MyController>(c => c.Action(1));

}

I took the test as-is, and added the code required to make the test compile:

1

2

3

4

public class MyController

{

public IActionResult Action(int dummy) => null;

}

I expect the above test to compile, but still fail because the default route added by MVC expects the parameter of my action to be called id in order for the route to succeed. If we examine the UseMvcWithDefaultRoute call present in my website’s Startup class, we can confirm the default route is {controller=Home}/{action=Index}/{id?} (note it specifically looks for a parameter by the name of id). The test further validates this because it does in fact fail with the following message:

1

2

3

4

5

Test Name: MyControllerShouldHaveRouteForActionWithId

Test Source: <snip>\tests\Example.WebApplication.Tests.MyTestedAspNetCore\MyControllerTests.cs : line 11

Test Outcome: Failed

Test Duration: 0:00:00.565

Result Message: Expected route '/My/Action/1' to contain route value with 'dummy' key but such was not found.

That’s good. And changing the parameter name to id allows the test to pass as expected.

The alternate implementation is somewhat complicated because it is not possible to test routes in MVC directly without mocking and instantiating significant amounts of the MVC pipeline. Therefore, the advice is typically simply to run the test as an integration test, as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

[Fact]

public async Task MyControllerShouldHaveRouteForActionWithId()

{

var uri = "/My/Action/1";

var builder = new WebHostBuilder().UseStartup(typeof(Startup));

using (var client = new TestServer(builder).CreateClient())

{

var response = await client.PostAsync(uri, null);

response.IsSuccessStatusCode.Should().BeTrue(

because: $"{nameof(MyController)}.{nameof(MyController.Action)} should be reachable on '{uri}'.");

}

}

Whilst I suspect there are other ways to achieve the desired result such as directly testing MVC’s routing components, if not for my experience with ASP.NET Core already, the last test would probably have been a bit of a challenge to put together, despite the many examples available. What seemed so simple using ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’, is clearly a little more involved, and considerably less readable in the form I’ve provided above.

In actual fact, I utilised a number of helper methods I’ve built up over the last few months, so the test, when I first created it, only contained 3 lines of much more readable code; but I added the relevant helper method code to the test to show it fairly.

I want to say now, I didn’t write the above conventional code in any way at all to try and catch out ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ or vice versa. It genuinely is the practice we follow at my company to perform most of our tests. Clearly, the practice I’ve used is much more inline with what we consider integration testing, because the test will literally run the startup defined in my actual Web Site, it will actually host a web server, and then call into it with the specified URI and HTTP Content.

I was very surprised at first to see the result of that test:

1

2

3

4

5

Test Name: MyControllerShouldHaveRouteForActionWithId

Test Source: <snip>\tests\Example.WebApplication.Tests.Conventional\MyControllerTests.cs : line 15

Test Outcome: Failed

Test Duration: 0:00:00.578

Result Message: Cannot return null from an action method with a return type of 'Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc.IActionResult'.

I had accidentally created a controller that could not be used because you’re not allowed to return null, as decribed in the message above. What’s more interesting than the difference in exceptions here, is that MyController.Action is in fact called by the second test; it must be in order for MVC to recognise the fact that I’m returning a null. Which means, the second test has in fact routed to the controller with the dummy named parameter, whilst ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ did not.

The most important question then, is which of the two tests are correct?

I changed the controller implementation as follows:

1

2

3

4

public class MyController : Controller

{

public IActionResult Action(int dummy) => View();

}

Note: The parameter name is still dummy, however I am no longer returning a null.

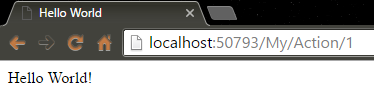

I then added the View as per normal MVC conventions and ran the actual website with the same URI the tests were using:

A big thanks to some unnamed friends for pointing out my obvious mistakes here, and especially to Ivaylo for taking the time to try and explain the error in my ways.

Yes, the request does in fact route to the controller action, but because my dummy parameter does not match the id parameter of the default route, and because the id parameter in the default route is optional, MVC has invoked the method with my dummy parameter unbound (i.e. dummy == default(int) == 0). Well, whilst obvious in hindsight, it certainly wasn’t what I first expected. Unless my Controller actually utilises the parameter somehow (echoing it back in the View or passing the parameter to another service) there is in fact no way for me to test the route binding with the Test Host in the manner ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ has. Or at least, I can’t think of a way.

I could of course delve into the routing mechanisms of MVC, but I assure you, having tinkered in routing, that would be far more involved.

(Preliminary) Conclusion

I intend to make one or two additional comparisons in my next article, testing out much more advanced features to ensure ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ is able to handle it. But, having spoken with Ivaylo and reviewed the implementation details of the Fluent API provided, I believe I’d be hard pressed to trip it up. The library certainly does things that would either be overly tedious and longwinded, or outright impossible using the mechanisms I’ve grown used to.

Hooking into the relevant MVC pipeline components when testing has numerous advantages (so long as it is done very well!). ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ really is a very good library, which serves only to make my conclusion ever more bittersweet.

Fluent

I don’t want to dwell on this aspect given my half-rant above, but how amazing would this library have been if it was a natural extension of Fluent Assertions!? I don’t know if it’s something that either Dennis or Ivaylo share an interest in, but as a consumer, it’s certainly something I would greatly appreciate. Hopefully, I can nag both of them to get some action on this!

Performance

Whilst it is not really evident in the test times shown above (which can hardly be considered anything like performance measurements!) ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ is much more intrinsically involved in sub-components of the MVC pipeline. I haven’t gone as far as confirming such, but I believe it safe to assume that ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ will provide a performance boost over the much heavier integration testing I’ve shown.

As a purist of pre-optimisation mantra, I tend to entirely ignore performance until it becomes a problem. However, I know it’s crucial that we keep test times to a minimum so that running ever-growing suites of them not become a burden. I haven’t hit such an obstacle yet, but should I ever do so, ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ would certainly make lowering test times much simpler.

Behaviour-Driven Development

One of the comparisons I intend to make in my next article is that of the conversion of a behaviourally driven test, which are the ones I typically use. Whilst I’m sure the unit scoped testing demonstrated above is important to many people, my company and I prefer the BDD approach. Our tests tend to reflect that and instead describe the behaviour that is important from a product owner’s point of view. Whilst that might entail a few assertations of the nitty gritty detail defined in the tests shown, it’s often much broader.

Whilst I’ve no doubt that ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ could make some of the finer nuances simpler, that’s also heavily where the library’s emphasis lies. Huge swathes of functionality would be unused by me and mine, which makes the cost much harder to burden.

Cost

We all like to be paid for the hard work we do. With the world of collaboration growing, and resources from online services to NuGet packages increasingly made available, it’s easy to forget how much work may have gone into a feature we take for granted. However, with regards to open source software, I’ve always been a strong believer in writing for one’s self. The packages I’ve published and repositories I’ve collaborated on have almost always related and contributed to the progress of a project at work, and in rare occasions where that isn’t true, the contributions have been towards projects of my own making, in my own time.

I don’t expect monetary reward to ever come about from any of them; in fact if any such project should become even mildly popular I would be much more grateful for the professional acknowledgment implied. The best way for an open source project to drive revenue, in my opinion, is for the industry to become sufficiently enthralled by their experience (and subsequent dependence). Such projects may receive donations from grateful enterprises and individuals alike. Equally pleasant are opportunities like that of Jon Channon, James Humphries, and Andreas Håkansson who were recently sponsored to update NancyFX to ASP.Net Core, and I’m sure they are not alone in these sponsorships.

The pricing model, as adopted by ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ has two problems, in my humble opinion. The first is that there are many well documented alternatives for much of the functionality, and a subset of the library’s features can easily be achieved because the MVC stack, in all it’s open source glory, is easier to penetrate than ever before. This will make it much harder for ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ to earn sufficient uptake and prominence which, in part, leads to the second problem. Those of us who regularly switch between internal commerical projects that would be required to pay for ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’, and open source projects maintained either in our “spare” time or in addition to our corporate activities, are left in a slightly difficult position.

I would struggle to justify the costs of something so easy to replace or replicate at work, making any expertise gained in out-of-hours activities of much less value. I would need to be aware of both sets of practices, and if I know how to do things the hard way, it makes much more sense to practice this out of hours and gain valuable experience which I could not only utilise at work, but better guarantee being a transferable skill should I move on to greener pastures (as opposed to fighting the same cost vs. value of ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ again and again).

More than that, the knowledge - albeit basic - of MVC required to form the more conventional tests is yet again well placed expertise in a technology stack I’m clearly utilising.

Summary

I’m grateful to see the .Net Core and ASP.Net Core ecosystem so quickly grow and thrive. The drive for technologies we all depend upon to move to Net Standard (or compatible, at least) has been something I’ve tried to help with for well over a year now, and something I hope to continue as time and work permits. Whilst the issues I’ve described may not make ‘My Tested ASP.NET Core MVC’ a great fit for myself and my peers (yet), it is certainly something I encourage people to contribute towards and keep an eye out for.

Thanks

I often seek advice whilst writing these blog articles, for which Dan Kirkham and Adam Lee often concede to my coaxing and help out. But a quick thanks to Jon Channon for his help and review of an earlier draft.

I also want to thank Ivaylo personally. Having conversed, I believe this article will be considered much more the challenge I intended (which he will no doubt overcome), than any form of discouragement. Furthermore, despite an almost scathing first draft of this article, Ivaylo was graceful enough to point out the inaccuracies that would have otherwise been somewhat embarrassing for me!