Clean Space - Neural Networks

This article is a work in progress!

If you have been given this url, I hope you can provide some early feedback for an article that is work in progress. I may also link to an incomplete page (to help me not forget), so apologies if you've arrived here by accident.

This draft was published: October 11, 2017

Check back soon for the complete article!

It’s been more than a year since I last talked about Clean Space, so I wanted to throw out this (lengthy!) post with a bit of a status update, as well as talk about something I’m working on with regards to Clean Space that others might find interesting. So there’s the first bit of information - work on Clean Space continues. Not as actively as I would like, but I have to balance work and living.

Sensor Projection of Unidentified Vessel

Sensor Projection of Unidentified Vessel MTRD-4482

I won’t say the game has come on leaps and bounds, it really hasn’t. I spent a long time getting annoyed at game frameworks for having truly awful APIs, even forked MonoGame twice to give it a decent Game Loop, DI and an eventing backbone before giving up on the framework completely (I actually have an incomplete blog post about this which I can go back and complete if someone expresses some interest). My current plan is to use ThreeJS for rendering which looks plenty capable, and supports the web application model required by the massively intensive processing requirements of certain game aspects.

Artificial Intelligence

If you have a better memory than I, you might recall 12-18 months ago that I explained how comprehensive the AI in Clean Space would be. The goal was “simple”, every single thing a Human would be able to do in-game, an AI would also be able to do, and vice versa. The AI(s) would have no more game state made available to it than a player, and perspective would be forced upon player and AI alike.

A lot of AI-like behaviour can, and often is implemented in the form of numerous rules that react to events. However, because I’m apparently glutton for punishment, and as the title of this article probably gave away, I’m not taking the easy way out. Instead, I’m using as close to real artificial intelligence as I can get, which means neural networks and deep learning.

Goals

The high level goals of Clean Space have never changed.

- I want a game that I want to play. If anyone else happens to enjoy it too, great. If I can make enough money from it to pay server costs, awesome. If I can make enough money from it to buy a GTR… one can dream.

- I want to learn a metric sh*t tonne. There are so many aspects to this game that it’s literally impossible for any single person to know them all; I want exposure to as much of that as I can.

- I want to set an example. I wrote an article some time ago about how I feel about the Game Industry. The software industry as a whole isn’t much better, but what’s exposed of the Gaming side is worse comparably, in my opinion.

Clearly, meeting any kind of timescales is not an example I’ll be setting. But I hope to provide some clean practices and perhaps frameworks, framework/engine integration, tech articles on Clean Space mechanics, and of course Clean Engine.

I haven’t defined a specific minimum viable product for Clean Space, because despite the talk about money above, I don’t care all too much if the game ever releases. It’ll come along, or not, when it’s good and ready. But that does mean progressing towards smaller goals and trying to keep up with an ever-evolving game design.

In this article, I want to focus on AI and show how it contributes towards the bigger picture.

Layers in your Layers

There are so many AI’s required to fulfill my vision for Clean Space, that I’m going to have to name them for this to next section to make sense. I’ll apologise in advance for constant interruptions to immersion as I explain how the AI vs. Player mechanics will work.

Let’s start our example with a space craft, in a stellar system. I’m going to jump straight to the vehicle’s AI and skip over all the AI involved in construction, crew allocation, objective creation and assignment, etc.

Engineering

Let’s say the space craft has 2 primary propulsion units (main drives, or engines if you prefer). The Chief Engineer, in addition to maintaining everything, has been plotting the characteristics of each engine. She knows that every engine has it’s own quirks, derived from the materials used, assembly quality, fuel purity, and so forth. These hidden variables no one but the game engine knows completely (which means the AI doesn’t know them either). However, by monitoring data that is available (temperatures, pressures, harmonics, specific impulse, acceleration curves, etc.) a skilled engineer will be able to predict to some degree of accuracy how the engines will behave when they’re put to various uses in the future.

Personally, I’m not the kind of guy that would enjoy plotting this data in a spreadsheet and speculating as to the maths. I really hope one day that a niche within a Clean Space Community does attempt this though. I’d be fascinated as to how close they could get to the actual implementation, which I’ll try to make complex and elusive enough so as to make it impossible to predict with 100% certainty. Players won’t be punished for not undertaking these tasks themselves though, the AI will truly be the best I can make it. It won’t have access to anything the player can’t get hold of, so it will be working within a perspective without visibility of the myriad of hidden variables that actually drive the calculations, but predictive machine learning should be very useful here.

Astrogation

Constant revisions by the engineer are being fed into astrogation. There are many ways to get from A to B in space. In modern day technology we often see amazing trajectories like this one (OSIRIS-REx):

Ignoring that this trajectory isn’t intended to get from A-B per se, it does make for a good example of how modern day space flight paths rely on very limited specific impulse and delta-v. Given Clean Space works with more futuristic technologies and much lowered constraints, getting from A-B doesn’t need to follow these spectactular orbital trajectories.

As such, there are several flight profiles available to an astrogator, which in turn were derived from machine learning, not necesarrily pure unadulterated maths. The astrogator is responsible for feeding space craft characteristics such as mass, and the engineer’s recommendations for drive profiles, and then teaching her machine learning algorithms how to plot a course. Profiles might be trained by rewarding the conservation of fuel or time, reduction of strain on equipment, accuracy of target orbit, accuracy meeting a target rendevous epoch, or whichever reward weights the astrogator chooses. Ultimately, the astrogator is trying to prepare her virtual toolbelt so that no matter where the Captain wants to go and how they want to get there, the astrogator is ready to make that happen.

Processing time won’t be unlimited, so prioritising which profiles are trained best and kept up to date will require the astrogator to understand the Captain’s objectives and whims.

In-flight, the astrogator will also need to account for impromptu equipment failures and disparity between predicted and actual drive profiles, not to mention she may not have all necessary orbital data to have correctly accounted for relativistic effects, so will need to be able to compensate and adapt.

Captain

Clean Space is about as sandbox, open-world as you can get. But, whilst you can do anything you want, that doesn’t mean you’ll be rewarded for doing so. Planets, governments, syndicates, corporations, etc. are trying to balance a huge number of responsiblities such as economics and security. There is no magic cash cow in Clean Space that swings a wand and introduces money into the economy everytime you shoot a magically spawned pirate space craft. That money has to come from somewhere (as would the pirate…).

Captain’s will have spent ample time learning other trades and have a good understanding of roles available to space craft (no insurer would allow an inexperienced unqualified plebeian to take control of such an expensive piece of equipment, nor would any player have the startup cash to outright buy such a vehicle). Which role the captain and vehicle fill will be a matter of preference and supply & demand. Not everyone can be a Military Captain if there is insufficient drive for security - the government will reduce the budget and the admiralty will reduce expenditure (including rewards), effectively prohibiting the expansion (or forcing a reduction in) Military capable vehicles.

The game engine will attempt to balance player short falls by introducing AI to fulfill roles players don’t want, but if there is no demand for a role, a player is going to have an all but impossible time filling said role.

As such, the Captain in our above scenario has objectives, some kind of role they understand and know how to be rewarded. The Captain has to rely upon all the other layers of AI above in order to fulfill those objectives, for example, as Search & Rescue, plotting a least time course to a vehicle in distress in order to collect a reward from the distressed space craft’s insurer or be compensated by the government for that role. Or, as a gargantuan hauler moving materials between ore processing plants and refined material factories.

Whatever the purpose, whether the Captain is played by an actual human or an AI, it’s unavoidable that somewhere along the chain, they’ll be reliant upon AI. Layers of them!

Breakdown

In order to achieve the above, the goal needs to be broken down into much smaller, simpler stages. There is no single AI, that I know of, that could do all of the above, and if there was, I doubt I could afford the ongoing server costs of keeping such a monster fed.

But, if we examine the smaller objectives of the AI layers, much more achievable goals can be set. The predictive machine learning required of the engineer predicting drive characteristics is quite a well known problem nowadays, so I’m going to gloss over that one.

The astrogation profiles however, that’s something I haven’t accomplished yet. I don’t even know if it’s possible. The rest of this article will detail my latest foray into neural networks tackling orbital mechanics.

Wish me luck…

Target

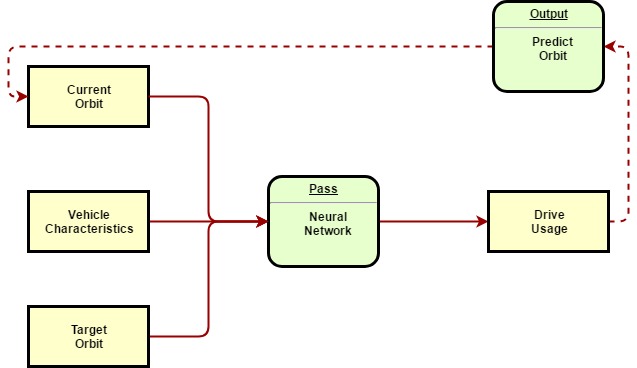

At a very high level, what I’m aiming for is the following:

Information relating to the current orbit of the vehicle and target orbit can be represented by orbital elements along with information regarding the equipment. A great many other factors may also need to be accounted for such as other orbital bodies, but we’ll aim for this, for now.

The intent is to feed all this information into the blackbox that is the neural network, which can spit out drive usage (i.e. when to use the drives, how much to use them, for how long, and in which direction). As was demonstrated in my lunar orbit article, it is often necessary to perform multiple burns in order to achieve a desired orbit, so it would be necessary for our drive usage to be able to be fed into a function that can predict the new orbit, which in turn could be passed back to the start to allow the network(s) to further refine the orbit.

Now, for those of you that know anything about machine learning and neural networks, it’s probably obvious that there are several flaws in either this high level plan, and even then, it is by no means a simple thing to achieve, even for an expert.

I am no expert.

Basics

Thanks to authors like Steven Miller and John Wakefield, plebs with no background or higher education (like me) have access to some great resources.

I know from reading through these and many other articles on the subject, that I should probably pick an existing framework. However, I won’t. Not because of any Not-Invented-Here stance, but because I really need to get to grips with how these mechanisms work. I don’t want to write a framework, but I do want to learn how they work.

So, my first steps are to create a framework that can handle the most simple of neural networks, the Single Layer Perceptron. To prove the fundamentals of my framework, I want to start with an easy challenge like that proposed by Trent Sartain, to create a network that can solve Exclusive Or (XOR).

I will do this by following John Wakefields tutorial series in order to progress solving Trent Sartain’s XOR challenge until the network requires something more difficult to work out. I won’t be copy/pasting any code, instead I’ll try to understand each phase of progress and then re-implement that myself (the reason for doing so is that, quite often, these very clever data scientists know enough about programming to make something functional, but their code isn’t as clean or even OOP as I would normally code, so I prefer to translate for my own sanity).

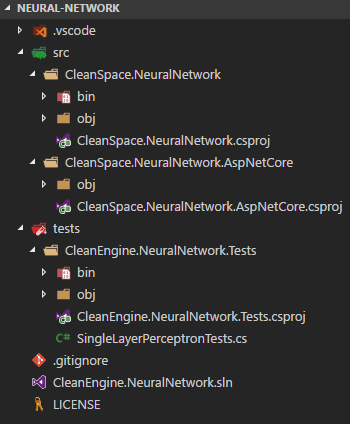

Speaking of OOP, having read a dozen articles I’ve already planned ahead somewhat, so if the following seems a bit overkill or the design decisions dubious, bear with it. I think they’ll be the right choice looking ahead slightly, as non-agile as that might be. I’ll start with the following structure:

My intent is to have the key services exposed within the CleanSpace.NeuralNetwork project and associated tests in the CleanSpace.NeuralNetwork.Tests project. The idea behind the CleanSpace.NeuralNetwork.AspNetCore is to provide integration with ASP.NET Core, providing middleware that can handle varying types of operations.

Having read a great number of articles and sample applications dealing with neural networks, one of my biggest code gripes is the configuration models the samples and frameworks exposed. Due to the complexity of neural networks, I’m going to avoid passing in magic numbers and strings as well as multi-dimension arrays and any manner of typically avoided code, in favour of a Fluent API. If I do have to provide strange arrays and such, the code will hopefully make it much clearer what they are.

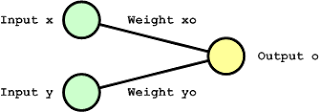

My first test will be an attempt to represent and prove John’s simplest network:

As you can see, there is no mysterious hidden layer in this network. It’s straight forward input to output in order to prove the code. This first test will try to train the network to always output 0, regardless of the input (as per Steven’s example).

The first problem is that networks rely upon a random distribution during initialisation. For those of you with any experience with automated testings, having random numbers flow through the test is a nightmare because it may cause the test to intermittently fail, reducing confidence in the test. To get around this, I’ll use a seeded random with a known seed (such as zero). That will give me a predictable / reproducable random distribution.

To represent the above network with a fluent API, I like to start with the Fluent Description first. I start with a fixture:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

using System;

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace CleanSpace.NeuralNetwork.Tests

{

public class ApplicationFixture

{

private readonly IServiceProvider _provider;

public ApplicationFixture()

{

_provider = new ServiceCollection()

.AddNeuralNetwork()

.BuildServiceProvider();

}

public NeuralNetworkBuilder CreateNetwork()

=> _provider.GetRequiredService<NeuralNetworkBuilder>();

}

}

The fixture being injected is very simple; I’m just using it as a composition root and abstract factory for the NeuralNetworkBuilder (via service location seeing as test projects don’t have a dependency injection bootstrapper like ASP.NET Core does). The test class itself is a bit more complicated, but its a test pattern I use for more complex projects:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

using FluentAssertions;

using System;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Xunit;

namespace CleanSpace.NeuralNetwork.Tests

{

public class SingleLayerPerceptronTests

{

public class Given2RandomInputs

{

private readonly Random _random = new Random(0);

private readonly NeuralNetworkBuilder _network;

private Given2RandomInputs(ApplicationFixture fixture) => _network = fixture

.CreateNetwork()

.AddInputs(_random.NextDouble(), _random.NextDouble())

.WithForwardPropagation();

public class WhenTargetIsZero : Given2RandomInputs, IClassFixture<ApplicationFixture>

{

public WhenTargetIsZero(ApplicationFixture fixture) : base(fixture) => _network

.AddOutput<double>()

.WithBackPropagation()

.Targeting(0);

[Fact]

public async Task ThenEachIterationReducesMarginOfError()

{

var firstPass = await _network.ExecuteOnce();

var secondPass = await _network.ExecuteOnce();

secondPass.MarginOfError

.Should().BeLessThan(firstPass.MarginOfError);

}

}

}

}

}

As you can see, I use xUnit Fixtures to pass in my ApplicationFixture (composition root) and hide some of that unimportant noise out of the way. I then build up a traditional Given-When-Then structure via classes. The important pieces add up to the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

_network = _neuralNetworkBuilder

.CreateNetwork()

.AddInputs(_random.NextDouble(), _random.NextDouble())

.WithForwardPropagation()

.AddOutput<double>()

.WithBackPropagation()

.Targeting(0);

var firstPass = await _network.ExecuteOnce();

var secondPass = await _network.ExecuteOnce();

secondPass.MarginOfError

.Should().BeLessThan(firstPass.MarginOfError);

As you can see, I’m using a Fluent API to build up the network, then executing the network a couple of times and asserting that the MarginOfError is reducing after each iteration. As a TDD developer, I wrote all this test code without having created any implementation, so I had nothing but compilation errors at that stage.

Creating the Fluent API implementation is a bit tedious but given I’ve done them before, I avoided some of the common pitfalls. The observant among you may have noticed that I haven’t given any details in the test for how forward and back propagation should work. That’s because I want to provide some basic defaults based on the aforementioned neural network tutorials, and later expand the core library with additional implementations and provide extensibility for custom implementations.

All of the above can be passed by creating some empty methods to satisfy the compilation errors and then setting MarginOfError to the next number in a decrementing sequence each time ExecuteOnce is called. I had to add a load of unit tests to flesh out some more thorough behaviour which I won’t detail in piecemeal here (you can go check out the code if you want nitty gritty detail).

Clearly, the network doesn’t have a hidden layer in the above network, so I wanted to make the code extensible enough to have one or more hidden layers without going beyond the realm of the test. Fortunately, following SOLID kept things on track and saved me some lengthy refactoring later.